En Seumeillant: Reflections on a 14-century French Ballade

For wind ensemble, (2014, rev.2017), 14’30”

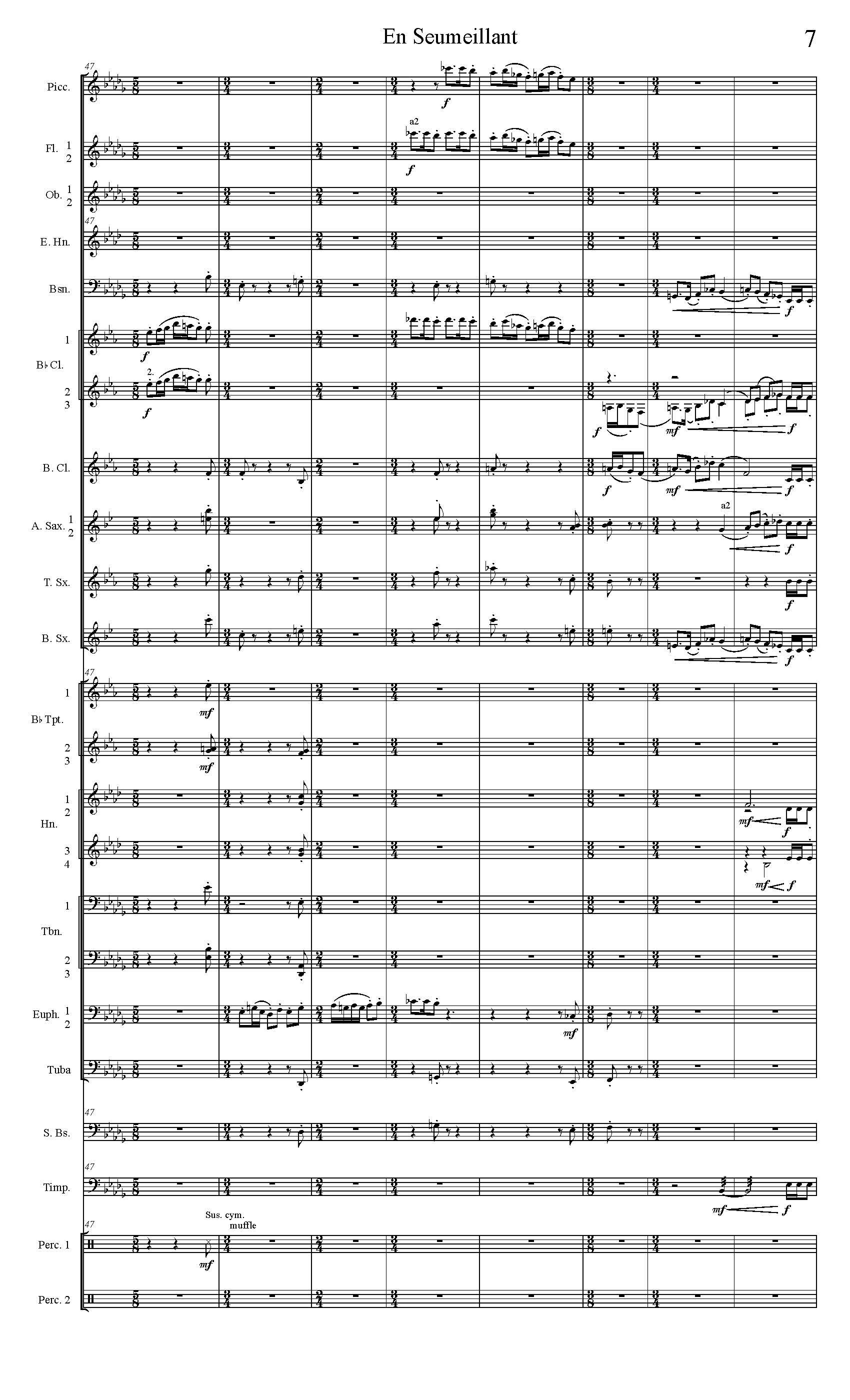

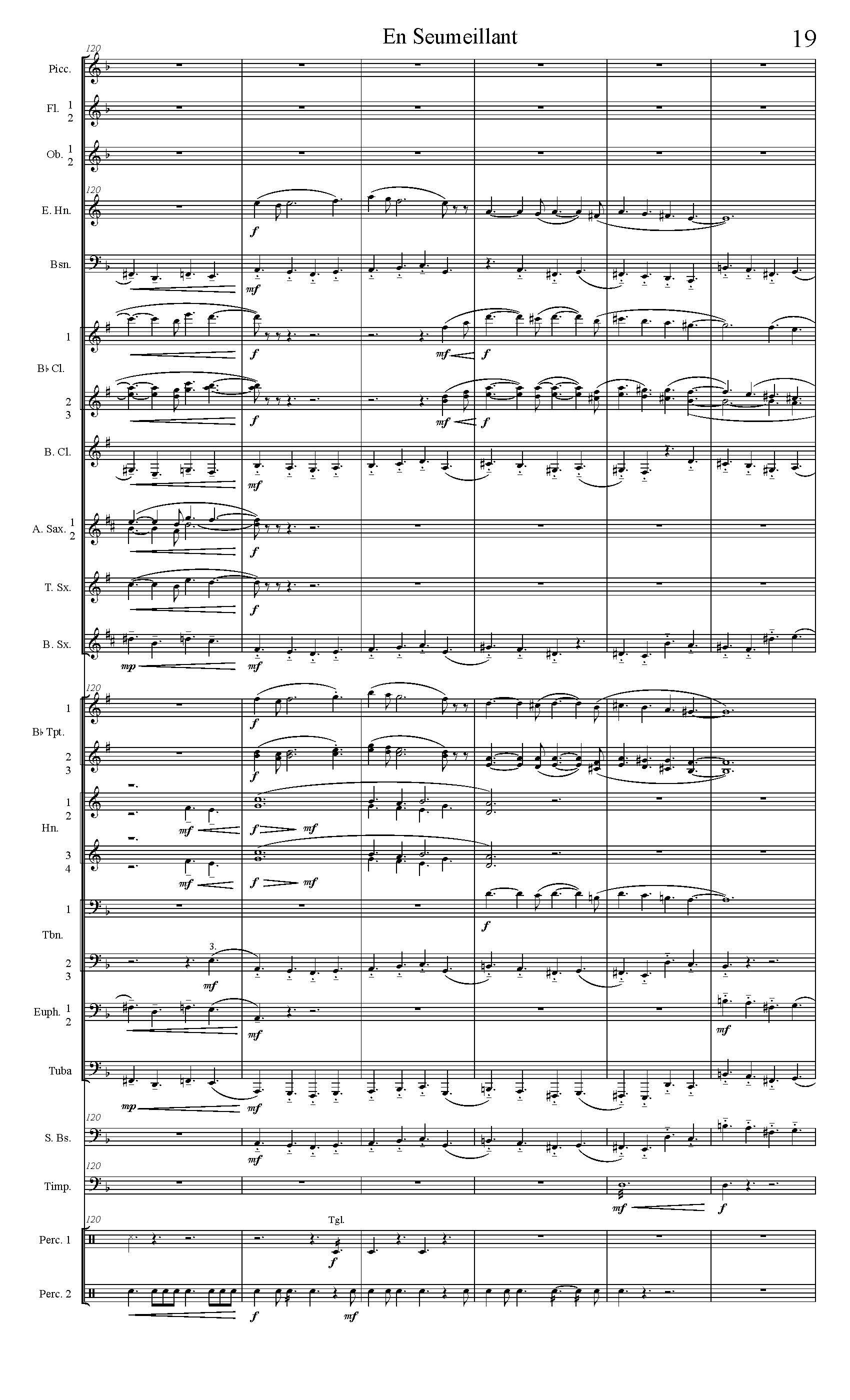

picc.2fl.ob.corA.bsn.3cl.bcl.2asax.tsax.barsax-3tpt.4hn.2tbn.btbn.3euph.tba-string bass-timp.2perc

Commissioned by Music Director Christopher Baum for the Manhattan Wind Ensemble.

Premiered March 2, 2014, New York, NY; Manhattan Wind Ensemble, Music Director Christopher Baum.

Program Notes

The composer known as Trebor (Robert backward) was one of the practitioners of the late 14th-century school of the ars subtilior. Hallmarks of the style include modal flexibility, chromaticism, and perhaps most strikingly, a remarkable rhythmic complexity including heavy use of syncopation. Less sympathetic ears have labeled the music of the ars subtilior “elitist,” “mannerist, and “decadent.” I find it thrilling.

The title of Trebor’s En Seumeillant translates as “While Dreaming.” The “dream” turns out to be a celebration of military conquest and chivalry, but the tonal instability and off-kilter rhythms give the piece a certain misty quality.

My work follows, if quite broadly, the form of a reverse theme and variations, whereby the source material, somewhat tweaked melodically, is revealed only gradually (D’Indy and Tenney provide other examples of the reversed form). The first third of Trebor’s 3-voice ballade is played almost verbatim (with extra doublings) by the brass near the end of the piece. Leading up to this point, different permutations of the ballade’s vocal lines—the top voice is featured most prominently, but not exclusively—are tossed about the ensemble and elaborated. Inversion, retrograde, diminution, augmentation, etc., are used, but in an extremely free manner. The secondary form of a palindrome (ABCDCBA) should also be perceivable, though with a severely abbreviated return of C and B.

The harmonic language takes off from the modal world(s) of the original and, significantly, of its various forms. The A sections, for example, are permeated by Lydian-flat7 harmony, not common to 14th-century France, but strongly suggested by the inversion of the top vocal line. There are elements of medieval-ish parallel harmonies in my work, but also many moments of more modern and often quite dissonant music as well, especially in the central Chorale section. It’s also no accident that the most prominent role in the opening and ending of the piece is given to the saxophone section, instruments that prompt precious few associations with the Middle Ages. –Jonathan David